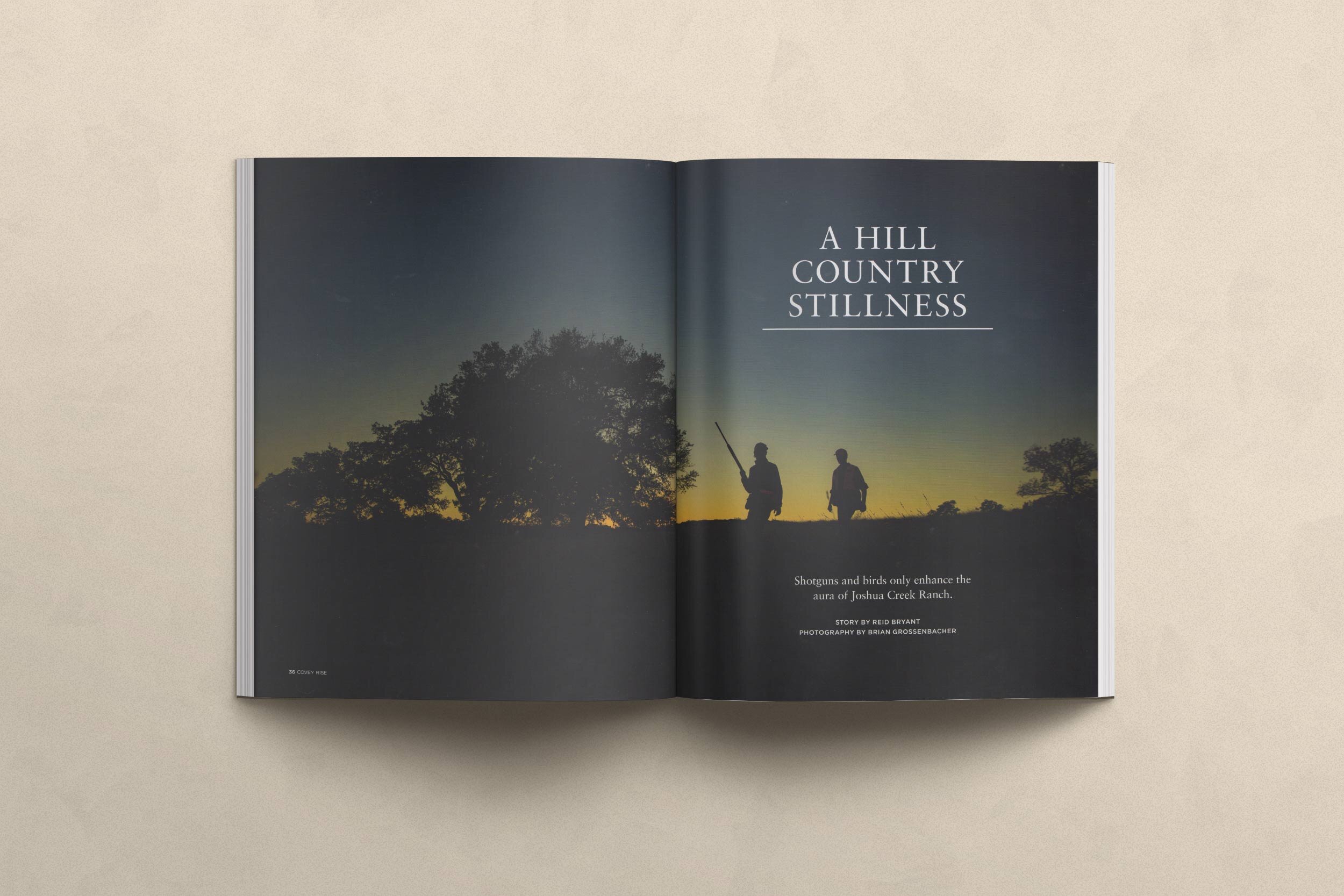

A Hill Country Stillness

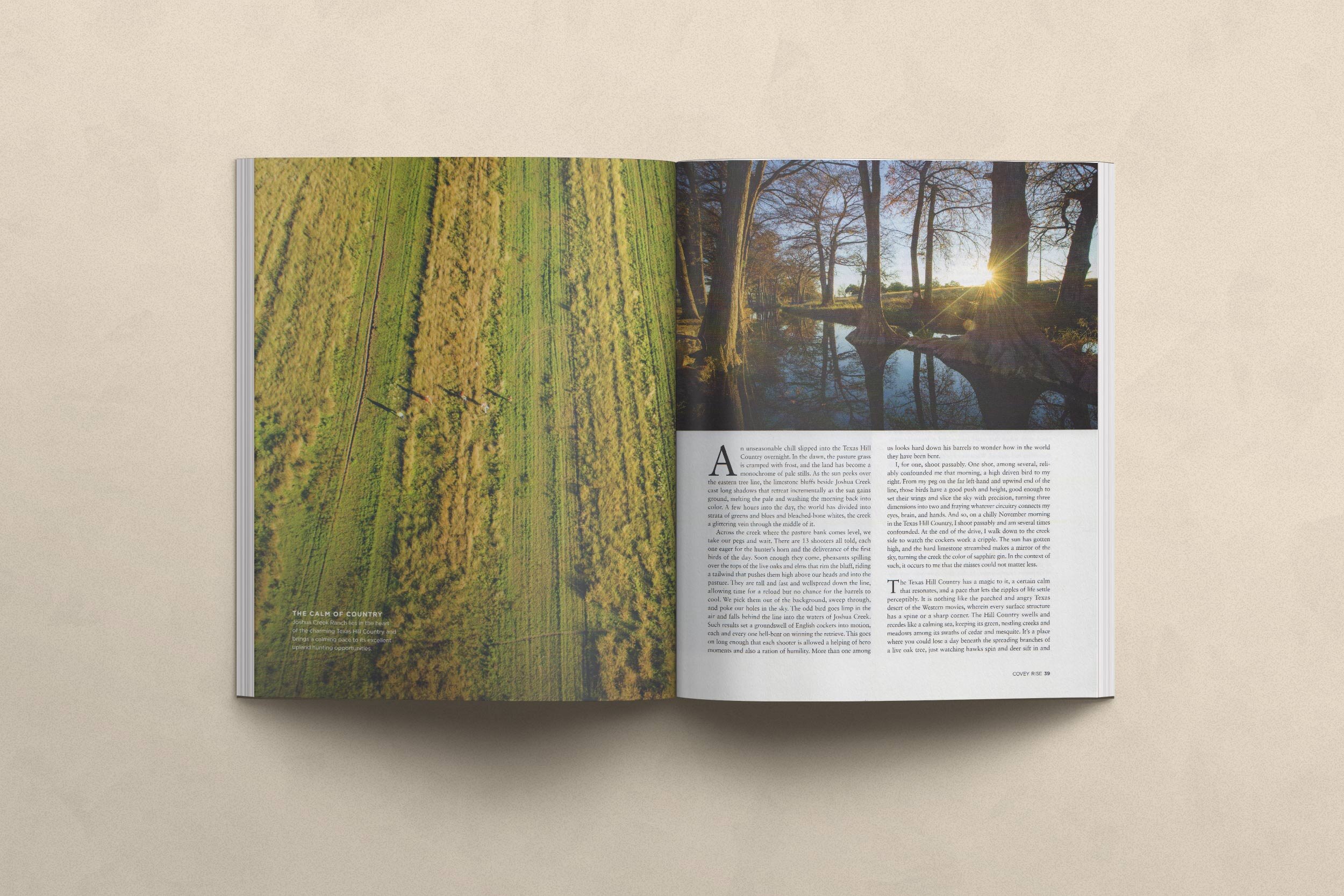

An unseasonable chill slipped into the Texas hill country overnight. In the dawn, the pasture grass is cramped with frost, and the land has become a monochrome of pales and paler-stills. As the sun peeks over the eastern tree line, the limestone bluffs beside Joshua Creek cast long shadows that retreat incrementally as the sun gains ground, melting the pale and washing the morning back into color. A few hours into the day, the world has become a stratum of greens and blues and bleached-bone whites, the creek a glittering vein through the middle of it.

Across the creek where the pasture bank comes level we take our pegs and wait. There are thirteen shooters all told, each one eager for the hunter’s horn and the deliverance of the first birds of the day. Soon enough they come, pheasants spilling over the tops of the live oaks and elms that rim the bluff, riding a tail-wind that pushes them high above our heads and into the pasture. They are tall and fast and well-spread down the line, allowing time for a re-load but no chance for the barrels to cool. We pick them out of the background and sweep through and poke our holes in the sky, the odd bird going limp in the air and falling behind the line, or better still into the waters of Joshua Creek. Such results set a groundswell of English Cockers into motion, each and every one hell-bent on winning the retrieve. This goes on long enough that each shooter is allowed a helping of hero moments, and also a ration of humility; more than one among us looks hard down his barrels to wonder how in the world they have been bent.

I, for one, shoot passably. There is one shot among several that reliably confounds me that morning, a high driven bird to my right. From my peg on the far left-hand and upwind end of the line, those birds have a good push and height, good enough to set their wings and slice the sky with precision, turning three dimensions into two, and fraying whatever circuitry connects my eyes and brain and hands. And so, on a chilly November morning in the Texas hill country, I shoot passably and am several times confounded; at the end of the drive I walk down to the creek-side to watch the Cockers work a cripple. The sun has gotten high and the hard limestone streambed makes a mirror of the sky and turns the creek the color of sapphire gin. In the context of such, it occurs to me that the misses could not matter less.

*

The Texas hill country has a magic to it, a certain calm that resonates, and a pace that lets the ripples of life settle perceptibly. It is nothing like the parched and angry Texas desert of the Western movies, wherein every surface structure has a spine or a sharp corner; the hill country swells and recedes like a calming sea, keeping its green, nestling creeks and meadows among its swathes of juniper and mesquite. It’s a place in which you could lose a day beneath the spreading branches of a live oak tree, just watching hawks spin and deer sift in and out of the timber. Joshua Creek Ranch, which occupies nearly thirteen hundred acres of hill-country bluff and pasture and juniper woods, is perhaps as emblematic of the region as any wedge of land, and definitively more serene. It lies among the bottomland ranches outside the town of Boerne, in the settlement of Welfare just north and east of San Antonio. The ranch occupies a piece of ground bisected by Joshua Creek itself, which etches its way north and gently east into limestone bedrock, tumbling into a dramatic marriage with the Guadalupe River near the ranch’s eastern boundary. The ranch road towards the main lodge parallels a creek-side lined with ancient cypress, among which mallards dabble and Guadalupe bass kiss midges from the surface. On a flat high above sit the spreading stucco buildings that host hunters, anglers, and those for whom a sporting adventure is complementary to the resounding tranquility of this place.

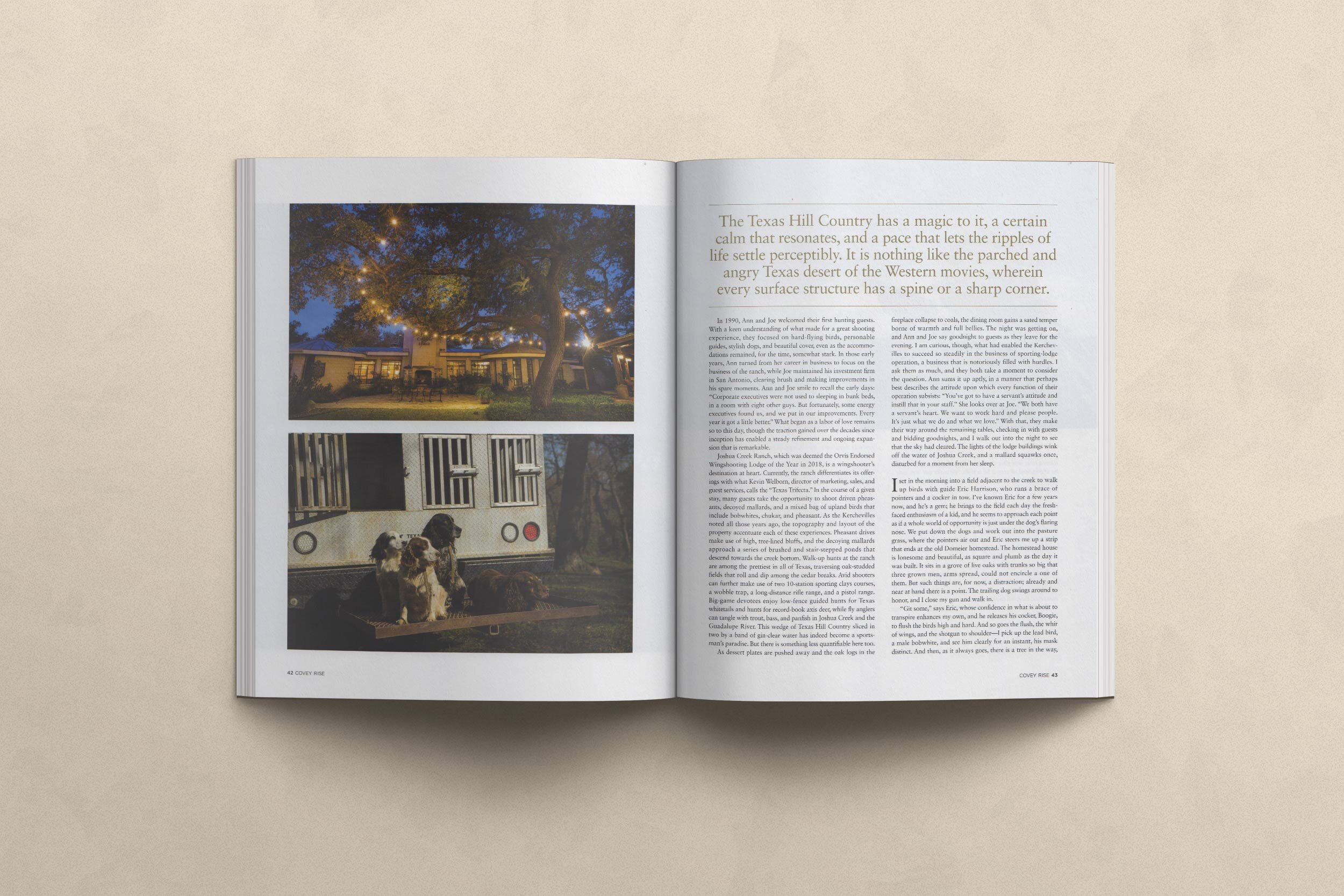

On the first night of my recent visit to Joshua Creek Ranch I sat down to dinner with owners Joe and Ann Kercheville, both of whom play an active role in the daily operations of the business. The night had grown chilly and spitting rain, but the main dining room of the ranch was aglow with firelight and the convivial spirit of people whose every need was being tended to, and every want anticipated.

As wine was poured and plates of butterflied quail presented, the Kerchevilles eased into the story of how this place came to be. Prior to buying JCR, the Kerchevilles had raised their children on a small farm near Boerne. Both were captivated by the region’s beauty, and in exploring the countryside they came upon the ranch, which was not at that time for sale. With the patience and persistence that has been a hallmark of their success, the Kerchevilles waited for the property to come to market. When at length it did, they made their move, fully intending to enjoy the property as a family ranch upon which they could raise a herd of longhorn cattle and let their kids experience the outdoor childhood that they themselves had enjoyed. “We stumbled upon this property, and we knew it was a very special place…” said Joe Kercheville, looking over at Ann, who nodded. “Even by hill country standards, the natural beauty of this place is overwhelming.”

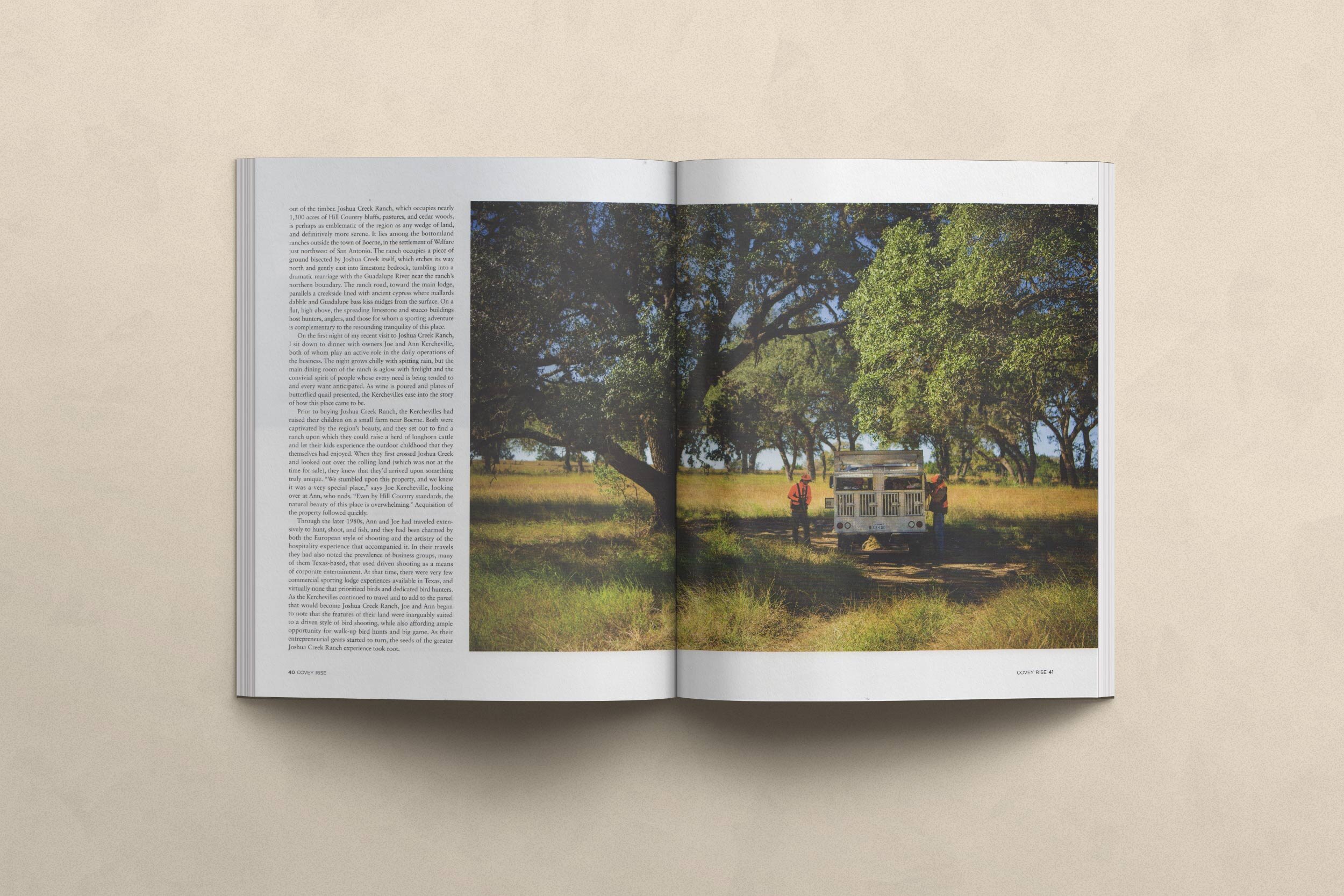

Through the later 1980’s, Ann and Joe had traveled extensively to hunt and shoot and fish, and they had been charmed by both the European style of shooting and the artistry of the hospitality experience that accompanied it. In their travels they had also noted the prevalence of businesses groups, many of them Texas-based, that used driven shooting as a means of corporate entertainment. At that time there were very few commercial sporting lodge experiences available in Texas, and virtually none that prioritized birds and dedicated bird hunters. As the Kerchevilles continued to travel and to add to the parcel that would become Joshua Creek Ranch, Ann and Joe began to note that the features of their land were inarguably suited to a driven style of bird shooting, while also affording ample opportunity for walk-up bird hunts and big game. As their entrepreneurial gears started to turn, the seeds of the greater Joshua Creek Ranch experience took root.

In 1990, Ann and Joe Kercheville welcomed their first hunting guests. With a keen understanding of what made for a great shooting experience, the Kerchevilles focused on hard-flying birds, personable guides, stylish dogs, and beautiful cover, even as the accommodations remained, for the time, somewhat stark. In those early years, Ann turned from her career in business to focus on the business of the ranch, while Joe maintained his investment firm in San Antonio, clearing brush and making improvements in his spare moments. Ann and Joe smiled to recall the early days; “corporate executives were not used to sleeping in bunk beds, in a room with eight other guys. But fortunately, some energy executives found us, and we put our improvements in. Every year it got a little better.”

What began as a labor of love remains so to this day, though the traction gained over the decades since inception have enabled a steady refinement and ongoing expansion that is remarkable. Joshua Creek Ranch, which was in 2018 deemed the Orvis Endorsed Wingshooting Lodge of the Year, is at heart a wingshooter’s destination. Currently, the ranch differentiates its offering with what general manager Kevin Welborn calls the ‘Texas Trifecta’. In the course of a given stay, many guests take the opportunity to shoot driven pheasants, decoying mallards, and walk-up mixed bag upland birds that include bobwhites, chukar, and pheasants. As the Kerchevilles noted all those years ago, the topography and layout of the property accentuate each of these experiences. Pheasant drives make use of high, tree-lined bluffs, and the decoying mallards approach a series of brushed and stair- stepped ponds that descend towards the creek bottom. Walk up hunts at JCR are among the prettiest in all of Texas, traversing oak-studded fields that roll and dip among the cedar breaks. Avid shooters can further make use of two ten-station sporting clays courses, a wobble trap, a long-distance rifle range, and a pistol range. Big game devotees enjoy low-fence guided hunts for Texas whitetail and hunts for record-book Axis deer, while fly anglers can tangle with trout, bass, and panfish in the Joshua Creek and Guadalupe River. This wedge of Texas hill country sliced in two by a band of gin- clear water has indeed become a sportsman’s Valhalla. But there is something less quantifiable here too…

As dessert plates were pushed away and the oak logs in the fireplace collapsed to coals, the dining room gained that sated temper borne of warmth and full bellies. The night was getting on and I’d be up early to shoot, and Ann and Joe would say goodnight to guests as they too left for the evening. I was curious, though, what had enabled the Kercheville’s to succeed so steadily in the business of sporting lodge operation, a business that is notoriously filled with hurdles. I asked them as much, and they both took a moment to consider the question. Ann summed it up aptly, in a manner that perhaps best describes the attitude upon which every function of the JCR operation subsists:

“You’ve got to have a servant’s attitude; you’ve got to instill that in your staff.” She looked over at Joe. “We both have a servant heart; we want to work hard and please people… it’s just what we do, and what we love.” With that, the Kerchevilles made their way around the remaining tables, checking in with guests and bidding goodnights, and I walked out into the night to see that the sky had cleared.

The lights of the lodge buildings winked off the water of Joshua Creek, and a mallard squawked once, disturbed for a moment from her sleep.

*

Joshua Creek meets the Guadalupe where the banks of both have crumbled away, and the limestone bluffs show porous white like bleached and weathered bone. On the Joshua Creek side and just upstream, a constriction marks the remains of a homestead dam. There, hand-cut blocks heave clear of the bank-side scrub and into the light of day, artifacts of a harder time made up of harder folk. The bulk of the dam is long since gone, but the steady passage of the creek speaks to patience and calm, and an underlying strength of place. There’s a confidence in that passage of water, and its ability to wash away rock; it’s comforting to know that some things of nature are eternal, while some things of man, even things heavy and hard-earned, are short-lived.

I set out that morning into a field adjacent to the creek to walk up birds with guide Eric Harrison, who runs a brace of pointers and a Cocker in tow. I’ve known Eric for a few years now, and he’s a gem; he brings to the field each day the fresh-faced enthusiasm of a kid, and he seems to approach each point as if a whole world of opportunity is just under the dog’s flaring nose. We put down the dogs and work out into the pasture grass, where the pointers air out and Eric steers me up a strip that ends at the old Dallmeyer homestead. The homestead house is lonesome and beautiful, as square and plumb as the day it was built, but now a hundred years empty. It sits in a grove of live oaks with trunks so big that three grown men, arms spread, could not encircle a one of them. But such things are, for now, a distraction; already and near at hand there is a point. The trailing dog swings around to honor, and I close my gun and walk in.

“Git some…” says Eric, whose confidence in what’s about to transpire enhances my own, and he releases his Cocker Boogie to flush ‘em high and hard. And so goes the flush; the whirr of wings and the shotgun to shoulder and I pick up the lead bird, a male bobwhite, and see him clearly for an instant, his mask distinct. And then, as it always goes somehow, there is a tree in the way, and it’s too late to pick up a trailer. I crack my gun and shrug and smile, and Eric does the same. With an easy indifference, he takes a long step after the dogs. “There’ll probably be more…” he allows, and of course he is right. We make our way into a sun-drenched morning, and there are more, and again I shoot passably, which is increasingly just fine.

Years ago, German homesteaders like the Dallmeyers found this land of sweet water and sweeping vistas and imagined a home of lasting peace, a promise of sanctuary. They exchanged peaceful settlement with the Comanche chiefs Buffalo Hump, Santa Anna, and Old Owl, in return promising to help defend the Comanche in the face of impending threat. We hunt our way up to the Dallmeyer dooryard and give the dogs a breather, and we look out over Joshua Creek, just upstream from the Guadalupe. The dogs have found a tank of water and they are drenched, and their tongues are lolling.

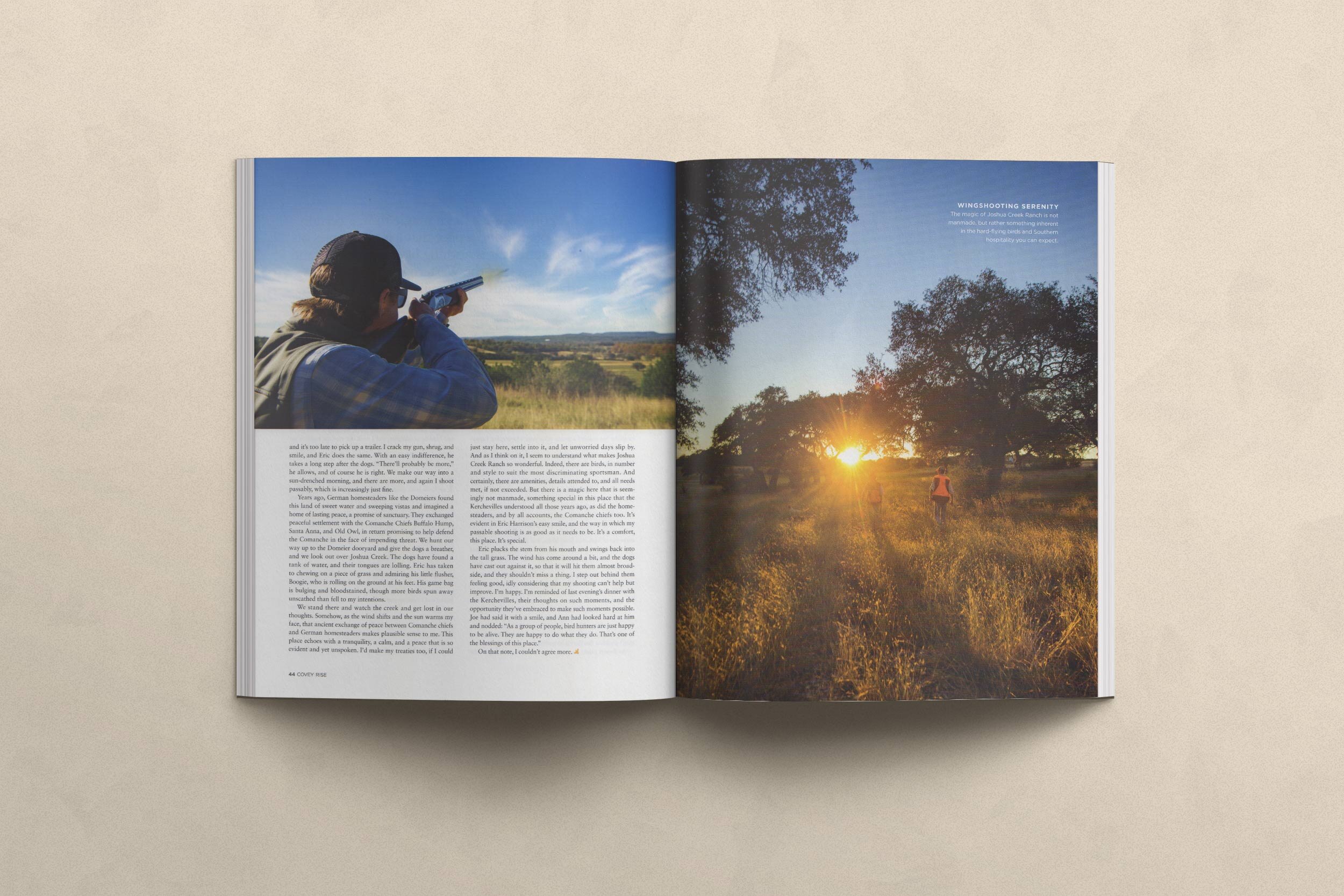

Eric has taken to chewing on a piece of grass and admiring his little flusher Boogie, who is rolling on the ground at his feet. His game bag is bulging and blood-stained, though well more birds spun away unscathed than fell to my intentions. We stand there and watch the creek and get lost in our thoughts. Somehow, as the wind shifts and the sun warms my face, that ancient exchange of peace between Comanche chiefs and German homesteaders makes plausible sense to me. This place echoes with a tranquility, a calm, a peace that is so evident and yet unspoken. I’d make my treaties too, if I could just stay here and settle into it, and let unworried days slip by. And as I think on it, I seem to understand what makes Joshua Creek Ranch so wonderful; indeed, there are birds, in number and style to suit the most discriminating sportsman. And certainly, there are amenities, and details attended to, and all needs met if not exceeded. But there is a magic here that is seemingly not man-made, something special in this place that the Kerchevilles understood all those years ago, as did the homesteaders, and by all accounts the Comanche chiefs. It’s evident in Eric Harrison’s easy smile, and the way in which my passable shooting is as good as it needs to be. It’s a comfort, this place; it’s special.

Eric plucks the stem from his mouth and swings back into the tall grass. The wind has come around a bit, and the dogs have cast out against it, so that it will hit them almost broadside, and they shouldn’t miss a thing. I step out behind them feeling good, idly considering that my shooting can’t help but improve. I’m happy. I’m reminded of last evening’s dinner with the Kerchevilles, and their thoughts on such moments, and the opportunity they’ve embraced to make such moments possible. Joe had said it with a smile, and Ann had looked hard at him, and nodded: “As a group of people, bird hunters are just happy to be alive; they are happy to do what they do. That’s one of the blessings of this place…”

On that note, I couldn’t agree more.