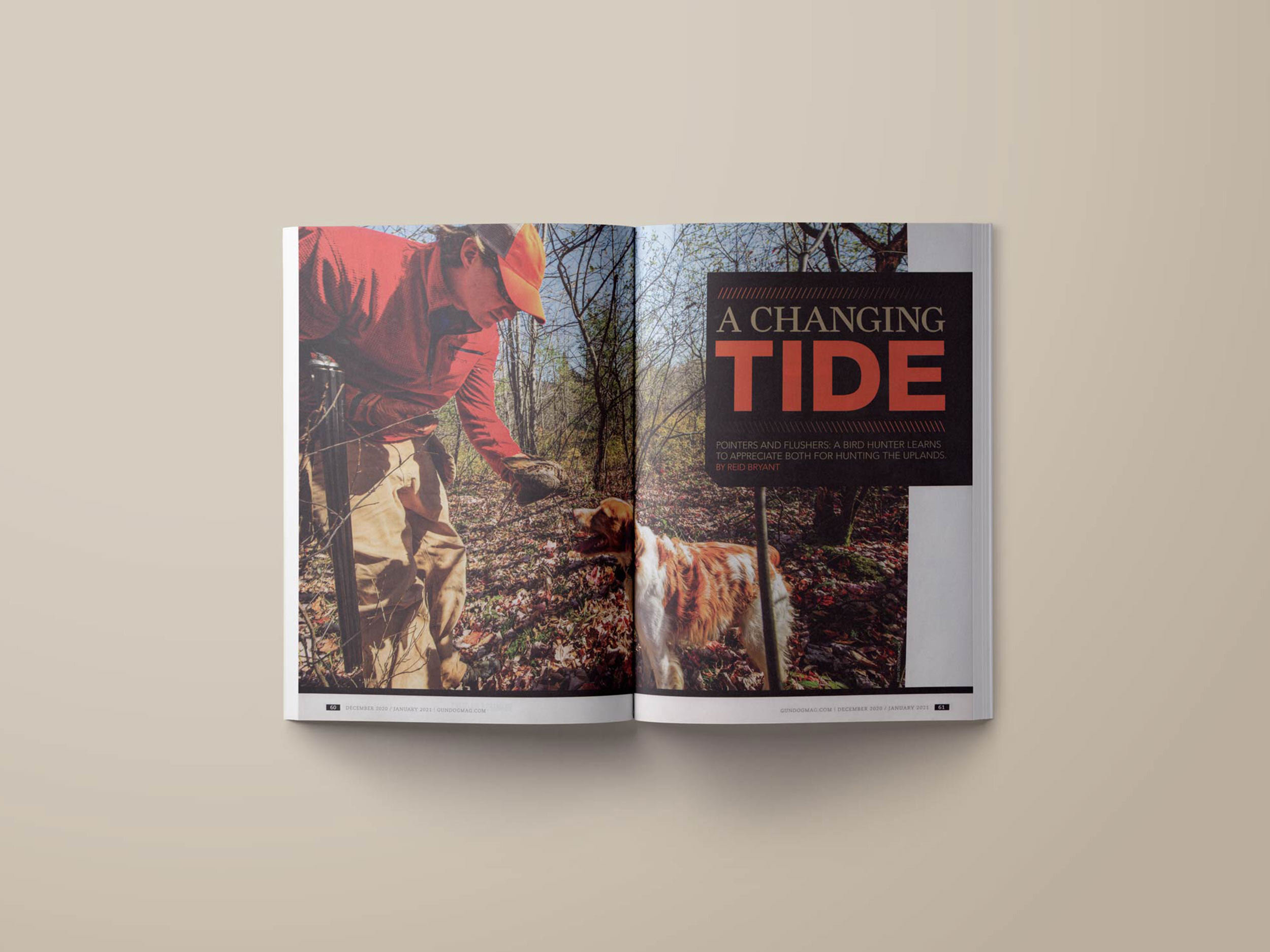

A Changing Tide

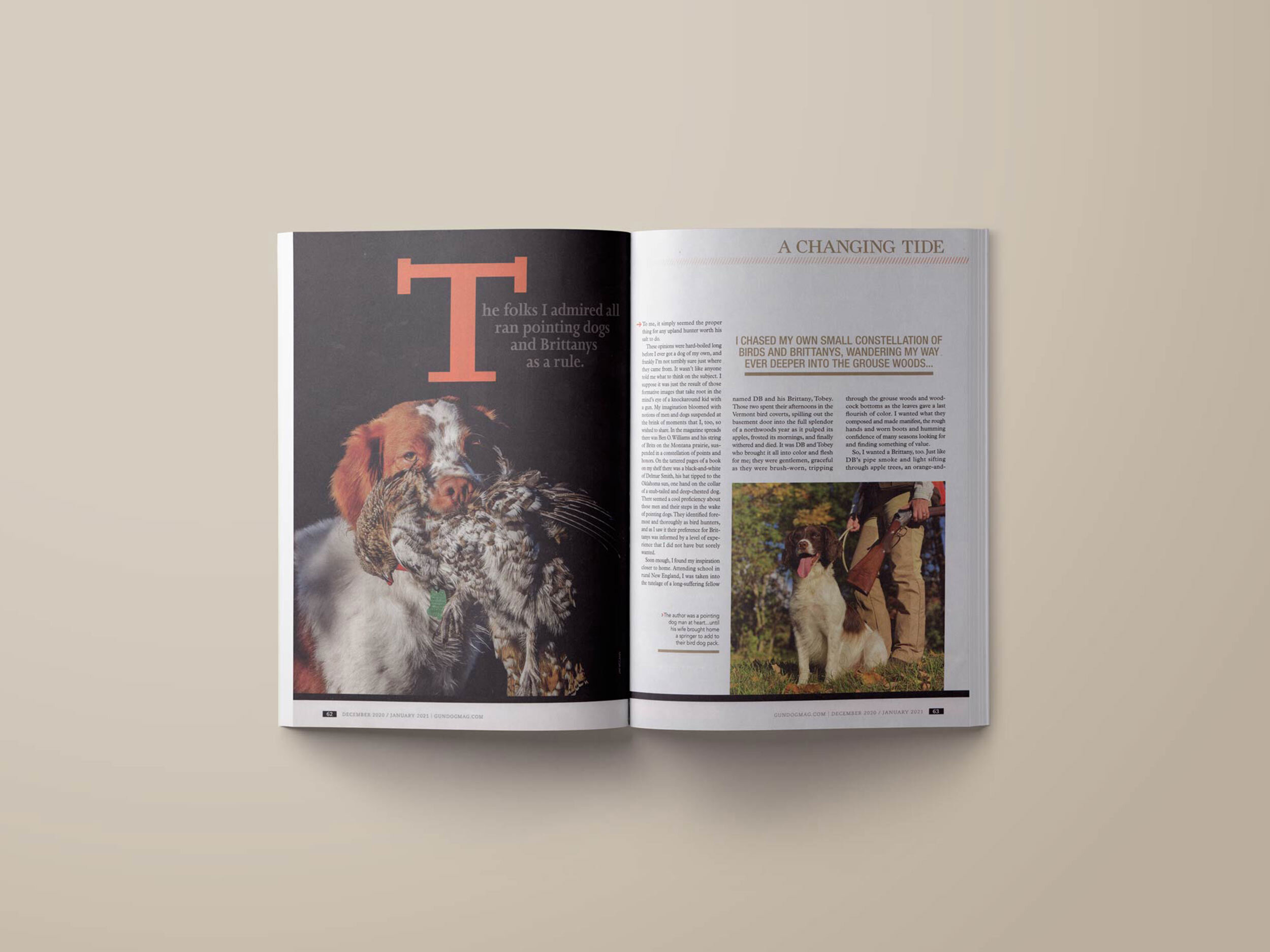

The folks I admired all ran pointing dogs, and Brittany’s as a rule. To me, it simply seemed the proper thing for any upland hunter worth his salt to do.

These opinions were hard-boiled long before I ever got a dog of my own, and frankly I’m not terribly sure just where they came from. It wasn’t like anyone told me what to think on the subject. I suppose it was just the result of those formative images that take root in the mind’s eye of a knockaround kid with a gun and some time on his hands, informing the journey forward. My imagination bloomed with notions of men and dogs suspended at the brink of moments that I too so wished to share. In the magazine spreads there was Ben O. Williams and his string of Brits on the Montana prairie, suspended in a constellation of points and honors, a covey of huns hidden somewhere in the bent stems and buffalo berries just upwind. On the tattered pages of a book on my shelf there was a black-and-white of Delmar Smith, his hat tipped to the Oklahoma sun, one hand on the collar of a snub-tailed and deep-chested dog. There seemed a cool proficiency about these men and their steps in the wake of pointing dogs: they identified foremost and thoroughly as bird hunters, and as I saw it their preference for Brittany’s was informed by a level of experience that I did not have but sorely wanted.

Soon enough I found my inspiration closer to home. Attending school in rural New England I was taken into the tutelage of a long-suffering fellow named DB and his Brittany, Tobey. Those two spent their autumn mornings making shavings in the woodshop, teasing Shaker furniture out of cherry boards while classical music played on a dusty, rabbit-eared Panasonic. The afternoons, however, they gave entirely to the Vermont bird coverts, spilling out the basement door into the full splendor of a northwoods year as it pulped its apples, frosted its mornings, and finally withered and died. It was DB and Tobey who brought it all into color and flesh for me; they were gentlemen man and dog, graceful as they were brush-worn, tripping through the grouse woods and woodcock bottoms as the leaves gave a last flourish of color then fell. I wanted what they composed and made manifest, the rough hands and worn boots and humming confidence of many seasons looking for and finding something of value, pinned on the point of their intentions.

So I wanted a Brittany too; just like DB’s pipe smoke and light sifting through apple trees, an orange-and-white dog with a bell on his neck just seemed to complete the picture.

It would take a few years. There was college to muddle through, and the distractions of youth, and then the necessary squaring off with responsibility, the reality of looking after something other than myself. The seasons unfolded as I tromped through the tangles alone, aspirations of dogs on point taking sharper focus in my mind as birds squirted out of the coverts ahead of my footsteps. When it all sifted out, however, I brought home a wiggly orange-and-white puppy. He slept on a blanket the cab of my truck until the day’s work was through and the autumn woods beckoned, and we could wander into them together. That pup tore through a few hunting coats with only slightly less zeal than he tore through the popple coverts of my New England. I followed his twisting path, and so I became a fair reckoning of the sort of bird hunter I’d always hoped to be. That he splintered my heart decidedly by running in front of a passing car one December morning was punctuation of what he meant to me, proof that stings even now. But loving and losing that dog afforded me conviction that only love and loss can do: I was a pointing dog man to the bone, and a Brittany man at that.

In the decade and more that followed, I chased my own small constellation of birds and Brittany’s, wandering my way ever deeper into the grouse woods in pursuit of the identity to which I’d pledged my faith. What I came to believe was that a pointing dog, chest to the ground and nostrils flaring, defined that sharpest sliver of anticipation, the promise of something in which I could find meaning, even as I poked harmless holes in the sky. But I also found that in following pointing dogs, as in constructing my identity and aesthetic as a bird hunter, I’d somehow become married to an ideal. I’d come to think that those frozen moments were archetypal, irrefutable, and something to be clung to. And as I clung to them, to my very identity as a pointing dog man, my wife came home one day with a Springer pup, and utterly gummed up the works.

At first I didn’t know what to think. I suppose that my leaning was to dismiss the pup as my wife’s miscalculation, something to be persevered and dealt with. But then of course she trained him and hunted him to success I’d never known, falling in with a crew who similarly loved the flushing spaniels, and the grouse and woodcock that they nudged into flight. And wouldn’t you know it, some of those folks carried two-barreled small bores just like me, proved sheer terror in the grouse woods like DB and Tobey, and looked upon their days following dogs with the same pose and poetry as Williams and Smith had embodied, all those years before. It made me stop and think, looking down at the liver-and-white conundrum that lay before our woodstove, paddling his feet in woodcock dreams that seemed destined to haunt my own.

The seismic shift took place one Autumn day amidst the stems of the Otter Creek Valley. It had been clear to that point that the Springer was my wife’s dog, hers to train and hunt behind, while I saw to the productive twilight years of our last and fading Brittany. The morning dawned cool and bright, the lower slant of the October sun making the maple leaves shine on the hillside. Our Brittany was gimpy and stiff that morning; he’d run the pockets of cover up Kirby Hollow the afternoon prior, and there was enough tall goldenrod and blackberry in there to effectively hobble him for a day or two to come. He’d bumped a grouse at the top of the covert that I had heard but not seen, as was so often the case. He looked up at me from his bed as the young springer turned frantic circles by the door. We seemed to share an opinion about the little interloper, but I wasn’t about to let an October day slip past without a few hours in the woods. I looked at the Springer, and looked at my wife, and confounded myself by asking if she’d join me in taking him out for a spin. Her delight in the question was multi-layered but evident; she smiled knowingly, and got her boots and whistle.

We put the dog down at the head of a band of popple poles that spilled off into a soaked and uncut hayfield. The pup was still pretty green, but my wife heeled him into the cover and hupped him. She slipped the lead from his neck and tapped his head, and let him stretch his legs. She hupped him again. He minded the whistle pretty well, and looked at her intently. I loaded up and closed my gun, and she released him again.

That little dog vacuumed up the cover in tight, even casts, rarely stretching out beyond thirty yards, rarely slowing down. I watched him as he worked the ground, slicing between the poles in surgical fashion. In the middle of one of those casts he turned hard back whence he’d come, picking up the smell of something. His nose seemed to pull him along, his stubby tail whirling like a Dervish, his zeal coursing through him in a current. A few feet ahead of his nose a woodcock sprung and twittered up, rising through the poles and banking right. I poked at him and clipped one wing, watched him tumble, and the little dog broke in pursuit.

The bird managed to clear the hedgerow, fluttering down and lighting in the tall meadow grass at the far side of a gulley. It was one of those haystack needle recoveries that my old Brittany would have left up to me, but even as I tucked out of the popples I could see the wriggling brown bum of the Springer poking out of the grass. His aft end was soaked and mud splattered, his head and shoulders thrust in the thick stuff, and as I watched him he withdrew proudly, a bird in mouth. He bounced back to us and spat the bird at my wife’s feet, accepted his praise, and took back into the cover, ready to do it again. And in that moment, I found myself more than willing to follow him.

I’ve thought about my identity as a bird hunter often through the years. We upland hunters are just people after all (albeit slightly more refined than those who only chase the ducks and deer), and as people we seek to differentiate ourselves, to find our place in the landscape. In looking for our camp we seek guidance from what we love, what we take comfort in, what makes our hunting hearts sing. But so doing we sometimes form opinions, opinions that can calcify us, and limit the scope of our experience. I have always found convictions attractive, evidence of my starch and my willingness to commit. I suppose I’ve leaned into such convictions to find my own place in the landscape, to define its boundaries, providing myself some semblance of what and who I might be, or might become. But in the early years of middle age, a bouncy little dog with a nose for grouse and woodcock fractured some of those convictions, and revealed a whole new piece of ground, and a way to walk upon it.

I suppose I’m no longer a pointing dog man, or a Brittany man for that matter, like the people I admired and hoped to become. An orange-and-white dog still sleeps by my woodstove, deaf and creaky but happy, twitching through his dreams of days gone by. And perhaps I’m not a flushing man either, though as I write these very words that self-same springer is by my side, squelching the life out of a tennis ball with only slightly less vehemence than that which he turns loose upon the autumn coverts of our New England. And though the picture of myself as an upland hunter becomes a bit less clear, a bit more fuzzy through its margins, I’ve never found myself more in love with the game, or the role that dogs play in it. I find solace and conviction in the growing realization that there will be dogs to follow into my future, some freezing moments into slivers of turgid anticipation, some stirring moments into radiant flight. I’ll take them all, and love each one, however they come to pass.

First Published in Gundog Magazine